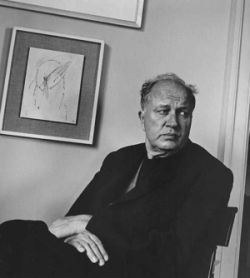

The descent into the organic life of things themselves dramatized the theme of regression that is explored in psychoanalytic terms in the book's title piece. "Sometimes, of course, there is regression," Roethke said in "An American Poet Introduces Himself and His Poems." "I believe that the spiritual man must go back in order to go forward." "The Lost Son" presented this regressive aesthetic in terms of both a descent into the subhuman life of nature and a return to repressed, childhood scenes. Karl Malkoff was one of the first critics to interpret these so-called "developmental poems" in terms of Roethke's divided attitude toward his father Otto, depicted, for example, in his widely anthologized work "My Papa's Waltz." Apparently, Roethke's filial anxieties stemmed from the trauma of Otto's death, which interrupted the adolescent's successful passage through oedipal rivalry. The five sections of "The Lost Son" work through the poet's conflicted attitude toward the dead patriarch and, by extension, what Roethke described as his "spiritual ancestors" of the literary tradition. Indeed, in a telling Yale Review essay, "How to Write Like Somebody Else" (1959), Roethke described his relation to W B. Yeats in terms of "daring to compete with papa." Roethke's drive to master his precursors, however, led him to forge significant literary innovations.

My Papa's Waltz

The whiskey on your breath

Could make a small boy dizzy;

But I hung on like death:

Such waltzing was not easy.

We romped until the pans

Slid from the kitchen shelf;

My mother's countenance

Could not unfrown itself.

The hand that held my wrist

Was battered on one knuckle;

At every step you missed

My right ear scraped a buckle.

You beat time on my head

With a palm caked hard by dirt,

Then waltzed me off to bed

Still clinging to your shirt.

~Theodore Roethke

For Roethke, boundaries between outer and inner dissolve; the natural world seems a vast landscape of the psyche, just as the voyage inward leads to natural things—roots, leaves, and flowers—as emblems of the recesses of the self. To travel either outward or inward is to encounter the self, and the voyage in either direction is fraught with the possibilities of transcendence, dissolution, or both:

In a dark wood I saw—

I saw my several selves

Come running from the leaves,

Lewd, tiny careless lives

That scuttled under stones,

Or broke, but would not go.